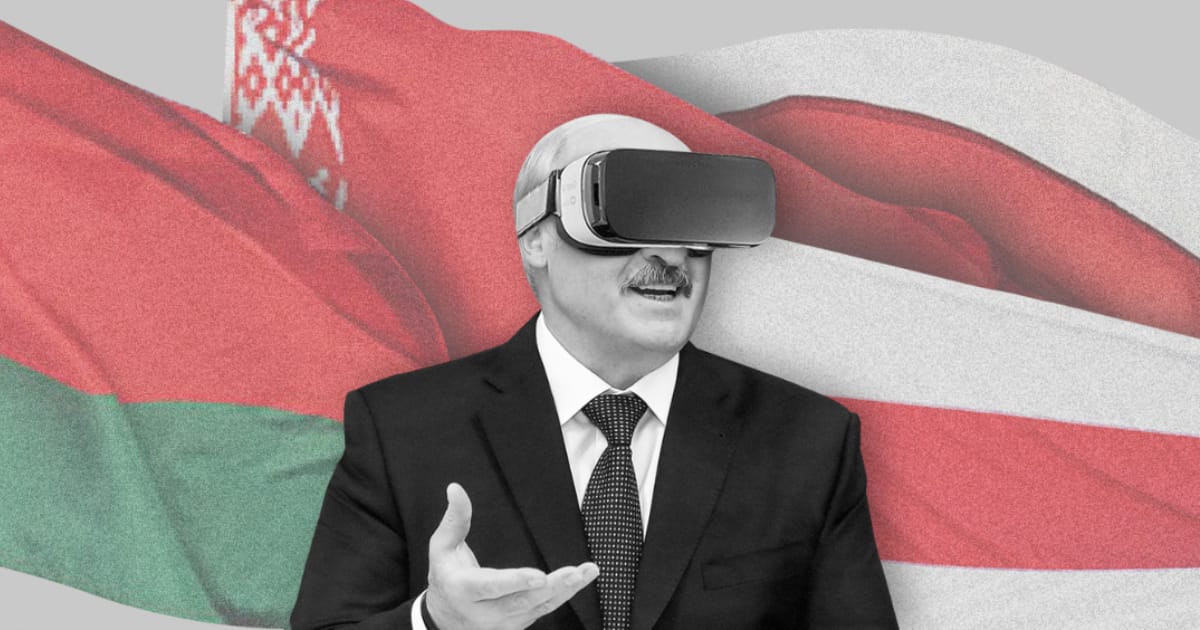

Techies on the barricades

Hello! This week our top story is a deep-dive into how the famous Belarusian IT sector is reacting to ongoing protests against President Alexander Lukasehnko. We also look at why the poisoning of Alexei Navalny has not led to an outcry, and investigate the rise of billionaire Tatiana Bakalchuk, who created ‘Russia’s Amazon’. We’d like to apologise for the lateness of this week’s newsletter — we were held up because of technical issues.

L'avenir du secteur des technologies de l'information du Belarus est en suspens dans un contexte de protestations

Tens of thousands of people protested Sunday across Belarus against President Alexander Lukashenko, the third consecutive week of demonstrations following heavily rigged elections. The country’s IT sector — famous for nurturing companies like World of Tanks and Viber — has traditionally kept out of politics, but they are now openly supporting the opposition. Why has the sector turned against Lukashenko? The Bell reporter Anastasia Stognei went to Minsk to find out (you can watch a Russian-language video report from her trip here).

Le secteur biélorusse des technologies de l'information connaît un grand succès

- The Belarusian IT sector is the only part of the economy to post any significant growth in recent years. This success — achieved despite Lukashenko’s moniker as the ‘Europe’s Last Dictator’ — have been widely reported on around the world, including by The New York Times, Forbes, The Financial Times and Wired. Major tech brands from Belarus include popular online game World of Tanks, and messenger Viber.

- Entre 2017 et 2019, les exportations de services informatiques du Belarus ont augmenté de près de 150 % pour atteindre une valeur de 2 milliards de dollars et, l'année dernière, les entreprises technologiques ont représenté près de 50 % de la croissance du PIB du pays. À l'heure actuelle, le secteur des technologies de l'information au Belarus représente jusqu'à 6,1 % du PIB du pays (en Russie, c'est moins de 1 %).

- Ce conte de fées informatique a commencé avec l'externalisation : EPAM est l'entreprise d'externalisation informatique la plus connue à avoir des racines bélarussiennes. Créée en 1993 par Arkady Dobkin et Leonid Lozner, deux camarades de classe de Minsk, elle est aujourd'hui cotée à la bourse de New York.

- Le boom des technologies de l'information dans le pays a été véritablement lancé par un parc de haute technologie (PVT). Il ne s'agit pas d'une "Silicon Valley" physique comme en Californie, mais plutôt d'un système de soutien financier aux entreprises informatiques. En juillet, le PVT comptait 886 entreprises employant plus de 63 000 personnes. M. Dobkin, de l'EPAM, est l'un des plus ardents défenseurs du projet.

- Ces dernières années, Loukachenko a revendiqué le succès du secteur des technologies de l'information. Mais les hommes d'affaires et les économistes qui ont parlé à The Bell sont unanimes : le plus que Loukachenko ait fait pour ce secteur a été de le laisser en paix (contrairement au reste de l'économie planifiée du pays, qui est de facto sous son contrôle personnel).

- Pourquoi Loukachenko a-t-il laissé faire ? Les théories divergent. "Il n'a tout simplement pas compris ce que c'était et comment cela pouvait devenir une industrie aussi cool", a déclaré Maria Kolesnikova, figure de proue de l'opposition et chef de cabinet du candidat à la présidence Viktor Babariko, actuellement en état d'arrestation. D'autres soulignent qu'il y a 15 ans, le secteur des technologies de l'information était trop petit pour être pris au sérieux et que personne n'imaginait qu'il pourrait devenir un tel foyer de pensée indépendante. Une troisième explication est qu'en 2011-2014, Loukachenko était désireux de changer le climat des affaires au Belarus et de réduire sa dépendance à l'égard de la Russie - il a donc autorisé la croissance du secteur des technologies de l'information en guise de contrepoids.

Soutien aux manifestations anti-Lukashenko

- For many years, there was no desire for political change among Belarus’ IT workers — but all that changed this month. For many Belarusians, not just in the IT industry, the pandemic was the last straw (Lukashenko dubbed the virus “corona-psychosis” and tried to ignore it). With the illness spreading rapidly, people found their own solutions and businesses began to organize themselves, creating mutual support groups, providing food for medics and printing masks on 3D printers.

- Dans le cadre des manifestations actuelles, des entrepreneurs en informatique ont collecté de l'argent pour les personnes détenues par la police et ont embauché et recyclé des activistes qui avaient perdu leur emploi. Lors des rassemblements, on peut voir des personnes portant des claviers peints du drapeau blanc-rouge-blanc de la Biélorussie précommuniste. Mikhail Chuprinsky, fondateur du fabricant de robots Rozum Robotics, a déclaré qu'il y avait beaucoup de travailleurs des technologies de l'information parmi les manifestants. Selon lui, il s'agit d'une "simple question d'économie" : avec le salaire d'un informaticien, il n'est pas difficile de se mettre en grève.

- "Tous les gens que je connais veulent faire quelque chose pour aider", a déclaré Mikita Mikado, fondateur de l'entreprise de logiciels PandaDoc. Il a promis une aide financière à ceux qui veulent démissionner des forces de sécurité. Rozum Robotics, quant à lui, embauche des habitants de petites villes qui ont été licenciés après avoir participé à des manifestations.

- Certains travailleurs de l'informatique se sont mobilisés contre le gouvernement avant même les manifestations actuelles. Plusieurs start-ups ont été créées pour surveiller les élections : Golos pour vérifier le décompte des voix, Bison pour collecter des données sur les violations des règles électorales et Honest People pour recueillir les témoignages le jour des élections. Elles ont toutes gagné des millions d'utilisateurs en l'espace de quelques jours, ce qui dépasse de loin la plupart des start-ups commerciales.

- Comme tous les Bélarussiens, les spécialistes des technologies de l'information ont été les premiers à constater la violence des forces de sécurité à l'encontre des manifestants. M. Chuprinsky, de Rozum Robotics, a déclaré avoir été battu lors de sa garde à vue de plusieurs jours. La police anti-émeute lui a crié dessus : "Combien t'ont-ils payé, salope ? Combien gagnes-tu ? Ça ne te suffit pas ? Si tu veux de la monnaie, voici de la monnaie pour toi !" pendant qu'il était agressé, a-t-il déclaré. L'entrepreneur a rappelé que les gens étaient battus en permanence en prison, leurs cris se poursuivant toute la nuit.

À sa sortie de prison, Chuprinsky envisage de quitter le pays. Il était loin d'être le seul. Toutes les personnes qui se sont entretenues avec The Bell étaient unanimes : si Loukachenko reste au pouvoir, le secteur des technologies de l'information au Belarus est fini. Presque toutes les entreprises prévoient actuellement de délocaliser. Le personnel du géant de l'informatique Yandex au Belarus commence à déménager en Russie, tandis que Viber a annoncé la fermeture de son bureau de Minsk. "Si nous ne gagnons pas cette bataille, le Belarus sera réduit en cendres", a déclaré Mme Kolesnikova, chef de file des manifestants.

Why the world should care Belarus’ IT sector is unique: it’s the only part of the economy in which the country can take genuine pride. If Lukashenko cracks down hard to quash the protests and cling onto power, the country’s IT industry will surely fall apart — and that would be a catastrophic blow.

Why Navalny’s poisoning didn’t lead to street protests

There’s been little change in opposition leader Alexei Navalny’s condition this week. He remains in an induced coma on a ventilator after being taken ill in what almost everyone believes to be a case of poisoning. He is now being treated in a German hospital. Despite the dramatic events, the reaction, in Russia and abroad, has been comatose: there are no mass protests demanding the truth about what happened, nor Western promises of more sanctions. Why not?

- Last weekend, Navalny was finally removed from the hospital in Omsk where he was taken after collapsing on a flight home from Siberia. He is now in Berlin’s famous Charité hospital. His airlift to Germany only took place after a struggle: the Russian doctors initially claimed he was too sick to be moved. Many believe that the doctors, under political pressure, were playing for time to ensure no traces of poison remained in Navalny’s body. Media outlet Proekt reported that the Kremlin was so concerned about the situation that it was receiving direct updates from the Omsk doctors.

- Navalny remains in an artificial coma, hooked up to a ventilator. His condition is serious, but not thought to be life-threatening. Perhaps more significantly, there are still no answers to the big question: what actually happened? According to German newspaper Der Spiegel, Charité has made a secret appeal to the German military to use their chemical labs in the hope of identifying the poison. The newspaper also reported that Chancellor Angela Merkel is getting daily briefings on the case.

- The response from the Russian authorities has been predictable, and no criminal investigation has been opened into the incident. The only change has been rhetorical: official statements on the Kremlin website now refer to Navalny by name (rather than the previously preferred formulation of ‘some opposition politician’). This might mean the Kremlin is taking the situation more seriously.

- Perhaps surprisingly, there has been little sign of public anger, save a few heated exchanges on social media. Economist and Navalny ally Sergei Guriev said that “everyone knows [something like] this can happen”, and that protesting is particularly difficult in the current climate.

- Western countries have condemned Navalny’s poisoning and some – most obviously Germany – have acted to help. But this is unlikely to lead to sanctions, according to Konstantin Sonin, an economist at Chicago University. “People in Russia might find it hard to believe, but European governments try not to interfere in Russian politics,” he said. Sanctions on Russia are generally only used in response to foreign policy issues, like the annexation of Crimea. To impose sanctions over a domestic political struggle is “unimaginable”, said Sonin.

Why the world should care Navalny’s poisoning helps you understand three things: the appetite for protest in Russia; how seriously the Kremlin views Navalny; and the likelihood of Western support for the opposition.

Beyond PR: how Tatiana Bakalchuk really created the ‘Russian Amazon’

Mother of four and former English teacher Tatiana Bakalchuk has set-up a Russian version of Amazon. She triumphed where many could not: both Sberbank, Russia’s biggest bank, and Yandex, the ‘Russian Google’ failed to replicate the success of the U.S. online retail giant.

Tous les reportages sur Mme Bakalchuk et son entreprise, Wildberries, donnent l'impression que leur histoire est un conte de fées : elle est aujourd'hui la deuxième femme la plus riche de Russie et vaut 1,1 milliard de dollars. Cependant, une enquête menée par The Bell a révélé que la vérité est un peu plus compliquée.

- Tout d'abord, nous avons découvert que le récit du "self-made" de Mme Bakalchuk avait été élaboré par une société de relations publiques. Lors d'un conflit avec des fournisseurs en 2017, Wildberries a engagé une équipe de relations publiques pour la première fois et il a été conseillé à Mme Bakalchuk de donner une grande interview, racontant comment elle avait construit son entreprise à partir de rien. Il y a peut-être une part de vérité dans cette histoire, mais il convient de noter que son mari, Vladislav, était déjà un homme d'affaires prospère lorsque Wilderries a été fondée et qu'il a gagné environ 5 millions de dollars en vendant une participation dans un fournisseur d'accès à l'internet. Les représentants de la société ont déclaré que cet argent n'avait joué aucun rôle dans la création de Wildberries.

- Au départ, le partenaire de Bakalchuk était un mystérieux culturiste, Sergei Anufriev. Selon les sources de The Bell, au début des années 2000, alors que la Russie disposait d'un marché gris florissant pour les produits importés, Anufriev a fourni à Bakalchuk un important lot de produits de marque Adidas. Personne ne sait exactement d'où vient ce stock, ni pourquoi plusieurs grossistes ont refusé d'y toucher, mais c'est le début du succès de Wildberries. Pendant un an, la société a pu vendre jusqu'à 50 % moins cher que les magasins Adidas officiels, selon nos sources. Par la suite, Anufriev a aidé Wildberries en matière de sécurité et de logistique.

- Au cours des années suivantes, le succès de Wildberries a résulté de sa décision d'offrir la livraison gratuite, de la création d'un réseau de points de collecte dans tout le pays et du refus d'acheter des marchandises de manière indépendante, au lieu de les vendre à la commission. Il s'agit du même modèle que celui qui a permis à Amazon de s'implanter en Occident. Mais ce n'est pas tout : nous avons parlé aux fournisseurs de Wildberries, qui se plaignent que l'entreprise utilise sa position dominante pour imposer des remises importantes et des ventes incessantes. Pour de nombreux fournisseurs, ce n'est pas rentable, mais il n'y a pas d'autre solution car Wildberries donne accès à un marché de biens aussi vaste.

In recent months, Bakalchuk has become a more public figure, and appears in the media. Even senior government figures boast of being her acquaintance, and apparently enjoy spotlighting Wildberries’ success. This summer, Bakalchuk appealed directly to President Vladimir Putin to support one of her company’s new projects.

Why the world should care We often write about successful businesses in Russia. Even if Wildberries’ backstory is not as clear-cut as its ‘rag-to-riches’ PR story might suggest, it’s still highly unusual. The company has become a market leader without any obvious political patron (if we discount a distant relationship with a former deputy Moscow mayor) and without state funding (although it does have loans from some state banks). Recently, Wildberries began an international expansion — so you might hear much more about it in the near future.